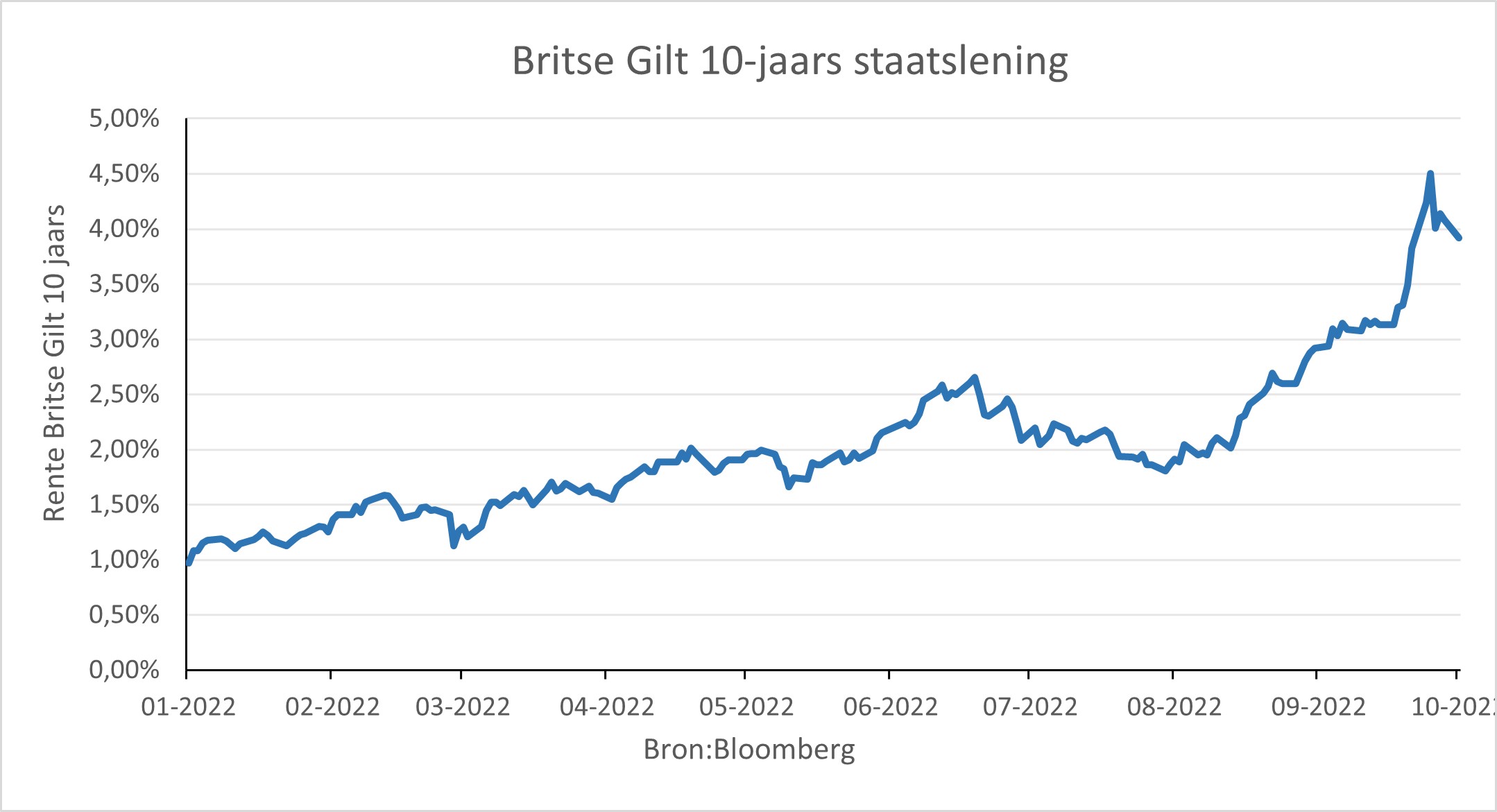

In these tense times, politicians throw colossal extra government spending or tax cuts into the fray to keep a more expensive life bearable for its citizens. In the United Kingdom, this went wrong in late September. Financial markets were so shocked by the announced, gross tax cut that interest rates went wild. As a result, pension funds were cornered as they had bought long bond contracts partly with borrowed money. These so-called Liability Driven Investments (LDI), when it came down to it, turned out to be mostly loss-making futures contracts, for which additional capital had to be paid in. Capital that was sometimes insufficiently available. The Bank of England had to act quickly to prevent worse. It announced an additional bond-buying program of 65 billion sterling, thus calming the bond markets.

Long term rate UK

In several countries, pension funds have sometimes rigged LDI programs. With these they try to hedge their future liabilities. In all countries with Defined Benefit systems, pension funds know approximately what they will have to pay out over a series of years (excluding indexation). Therefore, encouraged by regulators, they often decide to match part of estimated benefits with expected bond income. Because the funds almost never have that money to be paid out later, a fund often borrows some of those amounts and enters into swaps, kind of interest rate futures contracts, to create those interest and redemption structures over 20-30-40-50 years.

Even in The Netherlands, Europe’s richest pension country, LDI has become commonplace over the past 10-20 years. There are hundreds of billions in interest rate swaps outstanding. These have fallen sharply in value over the past year. In the meantime, many billions had to be paid into these swaps. Little is written about this silent pain for pension funds. Pension funds prefer to boast about the increased funding ratios, which are the result of higher interest rates. After all, with our Dutch calculation rules, the coverage ratio determines how much (inflation) indexation a pension fund can apply.

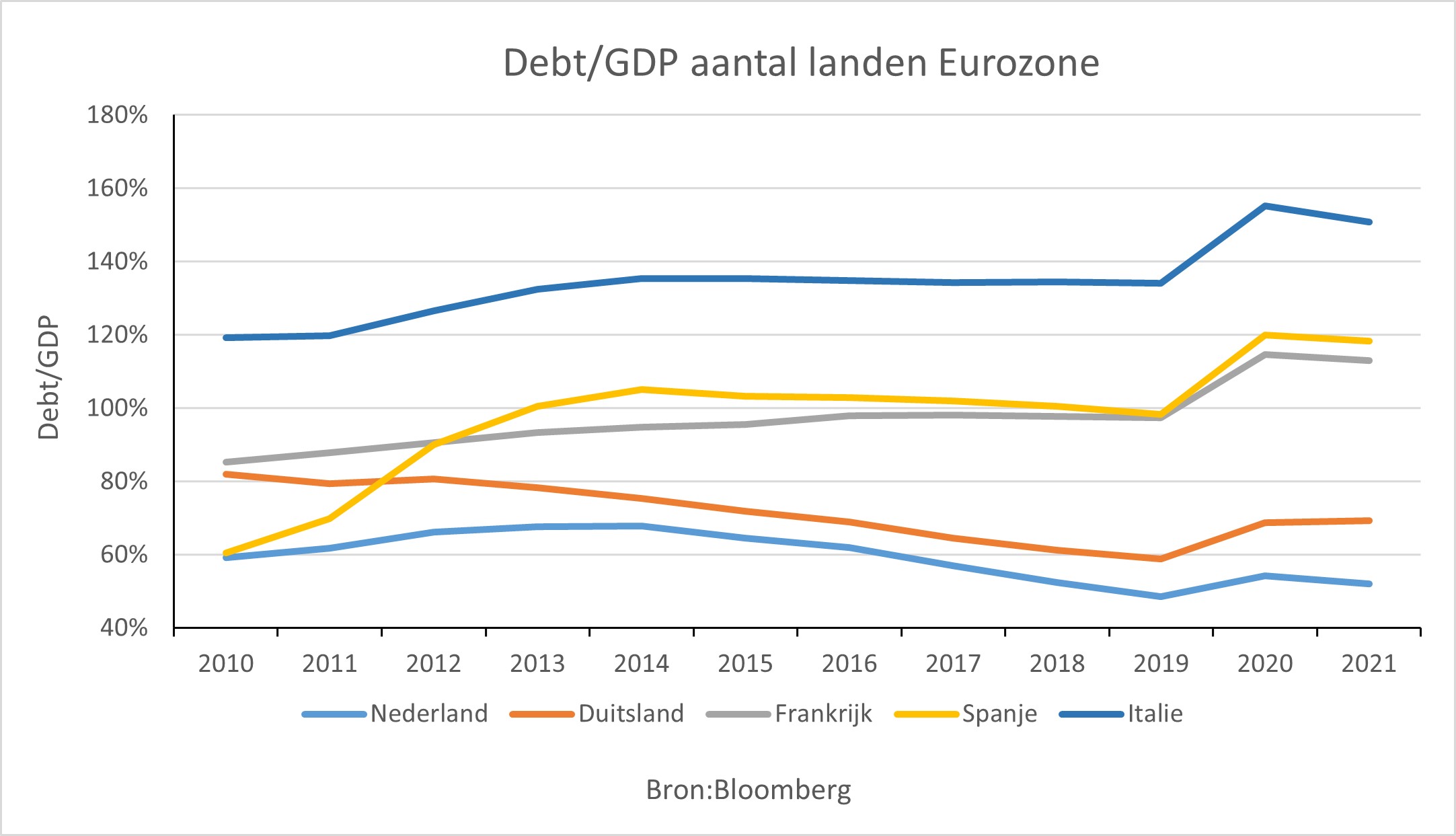

But what are politicians doing with public finances? Are they indeed keeping the confidence of financial markets? In Germany last week, a 200-billion-euro spending and borrowing program was announced to neutralize energy price increases. In The Netherlands it now amounts to about 25 billion, but of course that does not include such trifles as buying out the farmers (for 25 billion) and numerous other easily made fiscal commitments. Politicians still seem to think that money is almost free. In numerous European countries, public finances are deteriorating rapidly. Belgium, France, Spain, Italy, Greece: they are increasingly in trouble as fiscal rules are jettisoned (supposedly temporarily). Our euro zone will really have to start showing more fiscal discipline.

Government Debt versus GDP in the Eurozone

Ironically, the high national debt and increased interest rates limits the ability of central banks to swap their Quant Easing (QE) for Quant Tightening (QT). In good Dutch: to finally get rid of all the bonds bought over the last years. Because the higher interest rates threaten to get, the harder it becomes for pension funds. And then a central bank notices that it is easier to buy bonds (interest rate down) than to sell bonds (interest rate up). You name it, the ECB was also spooked by the British debacle last week.

By the way, the ECB also has a protective rampart against turmoil in bond markets. That rampart is called TPI (Transmission Protection Instrument). In the press, it was quickly turned into “To Protect Italy.” After all, if the interest rate differential between Italy and Germany rose too steeply once again, the ECB would be allowed to buy up Italian government bonds. That is what the TPI actually entailed. So again, no reduction of all those government bonds bought up in recent years, no QT, but still QE. Both in the UK and in the eurozone.

Politicians worldwide have for years become accustomed, perhaps addicted, to the notion of free money. Addicted to a central bank that kept buying up the debts they created. But now these government bonds are rapidly losing value and those same central banks have to report hefty losses to their politicians on all those bought-up bonds. Instead of the annual profit payment, the balance sheet of that central bank now has to be cleaned up with extra capital. That too takes some getting used to for politicians. Slowly it begins to dawn on them that money is no longer free, that more economical choices have to be made. And that they sometimes get in the way of central bankers: after all, that enormous extra spending is mostly inflationary.

Yet there is also a positive spin to this story. If central banks are limited in the size of their interest rate increases and their plans to resell bought-up bonds, then economic growth is also less squeezed. The same is true of the stock market downgrades that were mostly the result of the increased interest rates. Central bankers really do want to be strict, but if politicians threaten to destabilize financial markets, they will necessarily have to remain flexible. Moreover, interest rates can then fall a bit again.

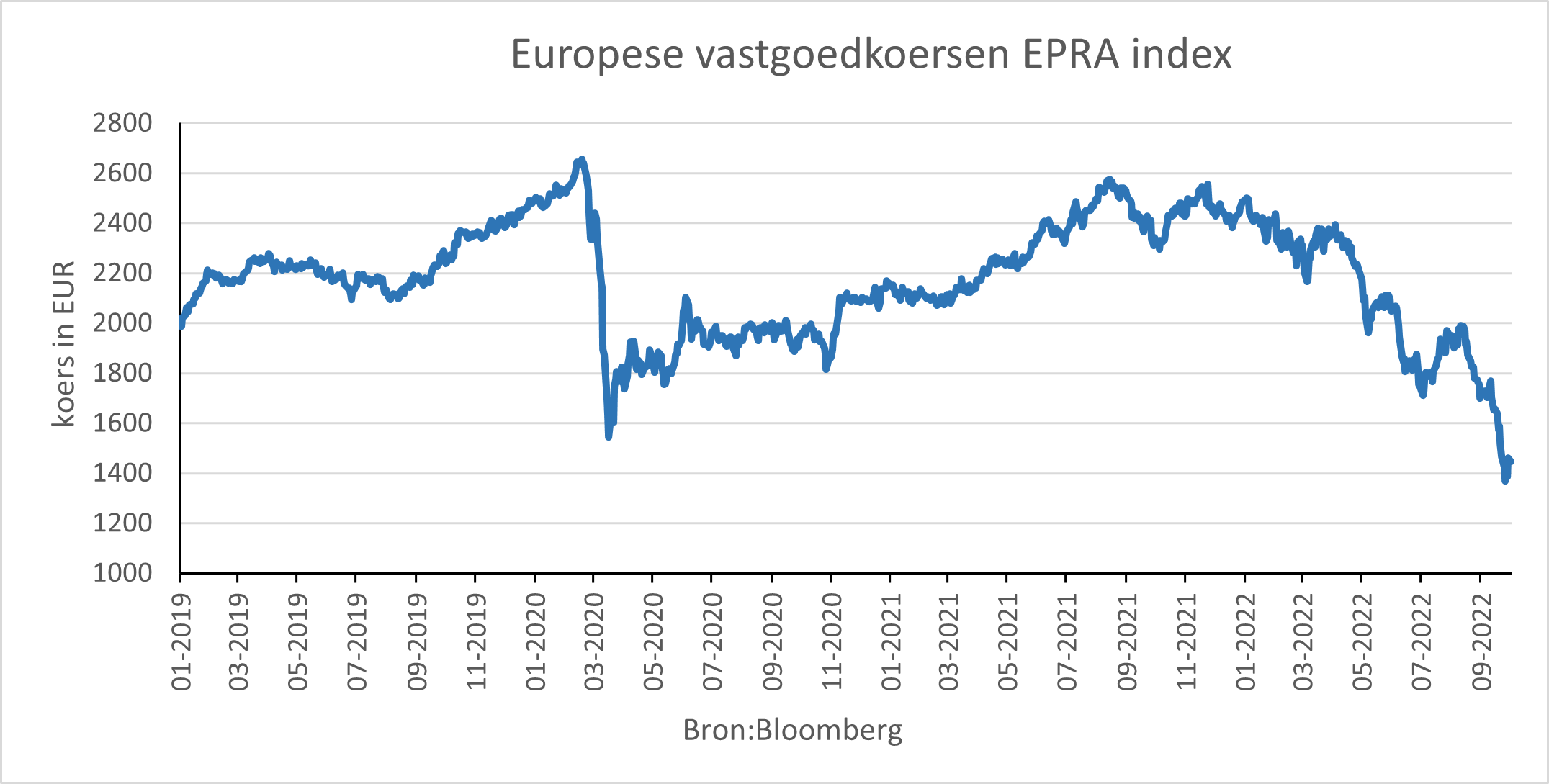

That is the “silver lining” that accompanies the cloud cover of the past month and, in fact, the entire past year. After lowering the equity risk in the portfolios in late July and late August, we halved our underweight position again in late September. We bought additional European and global equities at lower levels. We also bought a position in European real estate shares. Not that we have suddenly become hugely optimistic about these, but the price drop here this year (-40%) seems a bit excessive to us.

KReal Estate index EPRA

Meanwhile, we are increasingly asking ourselves at what interest rate level would we dare to buy long bonds again? Last month we gained some more and our 10-year yield ticked briefly up to 2.6%. By the way, at the time of writing this newsletter, only 2.1% of that remained. And how impressive is that when European (let alone Dutch) inflation is around 10% or more? Let’s hope central banks get inflation down to around 4-5%. Maybe then long interest rates will be around 4% again. Below that, long bonds do not seem attractive to us at the moment. We will stick with Private Debt, various forms of Alternative Fixed Income and our Real Assets, such as Infrastructure, for now. That is not free money, by the way; on the contrary, you fortunately get a hefty return for it in the form of interest and dividends.

BY: Wouter Weijand, Chief Investment Officer