Financial markets often exaggerate, making a “random walk” past the facts: if they ignore positive signals, pessimism prevails. When negative facts are set aside, optimism dominates. It is then up to us investors to identify which signals matter and which sentiment we should consider.

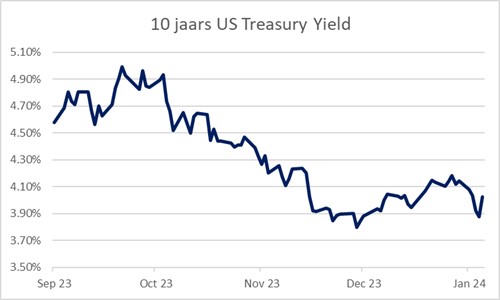

When Fed chairman Powell signalled last October, that he was just about done with his interest rate hikes, the market immediately assumed that interest rates would start falling quickly and sharply. And so, all bunches went off. However, Powell had never said this nor intended it that way. First, the battle with inflation really needed to be won, and with such a tight labour market and only slightly cooling economy, such optimism was not justified. Investors, including us for that matter, dared to buy long bonds again and collectively caused interest rates to fall by over 1% for roughly all government securities with maturities between 5 and 30 years. The irony of this lies in the substantial easing of monetary conditions (such as lower mortgage rates), which brings about such a rate cut. In fact, Powell does not have to do anything at all now in terms of monetary easing for a while, as the market had already done that for him right away.

10 years rate in the US since October last year

From mid-December, the market started to realise that its optimism was premature. It pushed long-term yields up again, adding 0.4% during January. For us, this prompted us to extend the duration of the bond portfolio again. We swapped short-term mutual funds for longer-term trackers of US government bonds, hedged to Euro. Thereafter, the market pushed down rates again.

Fed chairman Powell, nevertheless, can almost only disappoint. Market expectations for quick rate cuts remained sky-high, but in fact these lower rates are not needed for a while. Powell prefers to wait until inflation and wage growth are behind him. Adding to this was the news last Friday, that US employment rose by a whopping 353,000 jobs in January. The December figure had also been revised upwards. On that, long-term interest rates shot up again, from 3.8% to 4.1%. So, the bond market was very unsettled last month.

Europe

In Europe, interest rate expectations were at least as optimistic. It was thought that inflation would fall further quickly with such a weak economy and all those high inventories in the goods industry. Had the continued wage growth, which at +7% last year was among the highest in 40 years, been considered? Perhaps not, as inflation in Europe did not fall in January, but stabilised at 2.8% including energy and food and 3.3% for core inflation. With that, Lagarde can go on for a while with her current punishing monetary policy. Without an interest rate cut too soon, I suspect. In Europe, too, long-term interest rates therefore bounced back these days.

Impatience

The market is an impatient child: it wants all the goodies and especially now! This sometimes involves considerable opportunism, rising to speculative behaviour. But then again, that is what financial markets are for. Last month, chip giant TSMC from Taiwan presented bad numbers, but not as bad as the market had expected. Could the longer-lasting downturn in (non-AI-related) semi-conductors be over now? Share prices at ASML and a variety of companies linked to the sector shot up internationally. However, when major players like Intel and Samsung Electronics again published disappointing figures, it became clear that this downturn was not over yet. Still, stock prices in this sector only barely fell. So, optimism, especially in AI-related investments, remained high. Most notably at NVIDIA, which makes the very graphics chips that are so important for AI and seems to be growing fast.

This brings us to Big-Tech, the sector, which also dominated the news last month. Could earnings figures justify those ever-rising share prices? This remains to be seen. After the profit surges of the past few years, many big Tech funds are taking a break. At Tesla, profits, and growth in sales of its cars are stagnating. At Apple and Google, sales and profits were somewhat disappointing, and there are question marks over the high spending on AI policies, and it remains to be seen whether they will generate that much profit. Microsoft also suffered. Amazon and Meta, on the other hand, came out with fine figures, pushing their share prices up late last week.

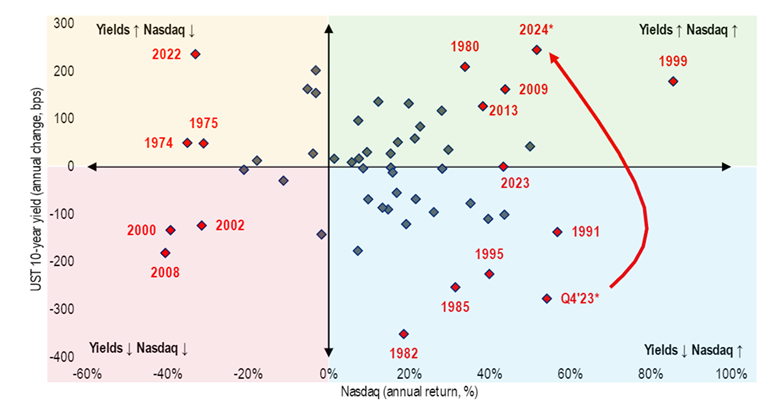

Many, including us, have long argued that fast-growing companies with high earnings expectations in the distant future should be especially sensitive to interest rate changes. After all, these affect the present value of those distant cash flows the most. But what did the practice look like over the past 50 years? Here is the work of Michael Hartnett of Bank of America, who linked the change in US 10 years interest rates to the Nasdaq’s earnings and highlighted the most striking results (through 26 January last year).

Interest rate changes and Nasdaq

In the upper left, you can see the combination of sharply rising inflation and interest rates and the fall of the Nasdaq. On the lower left are the recessions, with interest rates falling and the Nasdaq falling as well. Noteworthy is the upper right quadrant, with a sharp rise in interest rates and sharp rises in the Nasdaq’s share price. Something like this happened only during a recovery after a crisis or in bubble-like, i.e. speculative periods, like in 1999.

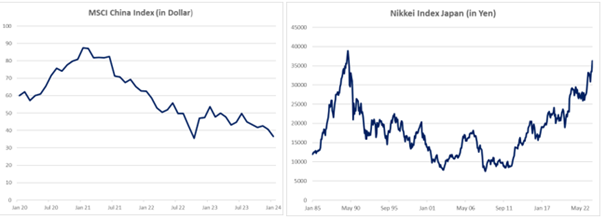

So much for the playing field of optimism. What about the playing field of pessimism, full of holes and pitfalls? If we talk about the danger of red-coloured stock market boards, we automatically come to China, which has excelled in this colour for some time. The combination of a real estate crisis plus government intervention in business almost brought the stock market, as well as the government itself, to its knees.

Because just like in Japan back then, when stock markets were so deflated, a sovereign wealth fund was announced last month, which was going to buy up shares with a lot of money (around US$ 280 bn). At least the effect of this news (the fund is yet to come) was that sellers stayed away for a while and prices could recover for a while. The real turnaround is not there yet. Then that bazooka, that big pot of money, really must come. The business climate may also become a lot friendlier. The market is still full of scepticism, pessimism still dominates. From a contrarian perspective, this offers hope for our Emerging Markets equity investments, which are often dominated by China and have disappointed in recent years.

In addition, let me put the Japanese market, which is far from our minds, but managed to turn exceptional pessimism into unbridled optimism. Here, the stock market fell prey to a tsunami of speculative behaviour in the 1980s, especially in Real Estate. When that house of cards finally collapsed, it took over 2 more decades, before stock market and Real Estate found their bottom, around 80-90% lower. Afraid of continued deflation, they decided to buy up both government bonds and equities. While elsewhere interest rates went up, Japan did nothing. This made the yen unattractive and so the currency quickly depreciated 40-50% in recent years. This, of course, ‘helped’ inflation up. Even wages are now starting to rise more seriously. Equities have been on the rise for some time, supported by the cheap yen, which strengthens corporate competitiveness. But you can also exaggerate as inflation is already hovering around 3-4% and the government is wholeheartedly encouraging its citizens to buy shares anyway, while the Nikkei Index has already risen from 7,000 to 38,000 over the past 15 years. And the period of interest rate hikes is now about to begin.

Battlefield or bubble?

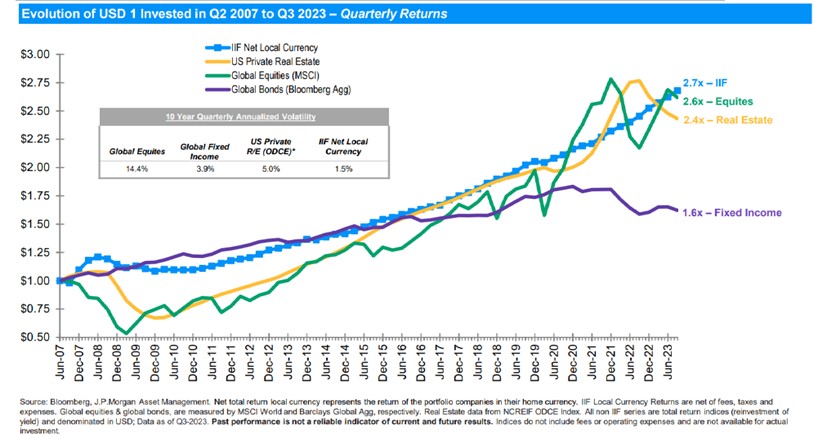

Behold our field of operations, which is sometimes a battlefield and sometimes a bubble. We navigate your and our ship through these markets, against the winds of exaggerated optimism or pessimism. Still, I like to show another middle ground, through a category of investments that stands out for being dull: infrastructure. Power plants, wind turbine and solar farms, port storage, pipelines, water companies, etc. Globally diversified, with around 1200 different assets, together around 40 bn in size. Below you can see in blue the results compared to equities and bonds from 2007.

Infra-fund (in blue), compared to equities and bonds

Part of the reason why performance is so stable is because the fund is not sensitive to stock market gyrations and valued only once a quarter. At the same time, there have hardly ever been any disasters and dividends have mostly been paid at 7% a year. Look at the chart and you immediately understand why, at US$ 120 million, we are already among the somewhat larger shareholders here. Fourth-quarter results were just announced: +3%. I call that a boring+ investment, which you rarely must worry about. Very much optimism or pessimism, on the other hand, is much more tiring.

Finally, there are circumstances, which the market does not know how to deal with and for which there are no prices. I am referring to wars, nearby or a bit further away. Conflicts, which vary in hopelessness, but are sad and costly, both in terms of loss of life and financially. But even of the latter, you see almost nothing in financial markets (yes, defence stocks rose sharply). So, are investors looking the other way en masse or are we just sticking our heads in the sand?

I don’t know, but I am not optimistic about these conflicts. I prefer that the pain of it also permeates stock markets, correcting something of the high valuations. Of course, you will say, that is also because we are cautious about equities. Yes, but wouldn’t it make more sense if we were already preparing a kind of Marshall Plan, with 1,000 bn to rebuild Ukraine, and another such amount to build our European defence, for which we must make a sacrifice over the next 10 years?

In the end, it is not about optimism or pessimism, but whether these major developments are priced into financial markets. Of AI, you may think that everyone is very optimistic, of China you may hope that people here are too pessimistic. But of wars, the market finds almost nothing. I hope people at least put a ‘price’ on it and that we all think about the longer-term consequences.

BY: WOUTER WEIJAND, Chief Investment Officer