Financial markets have long remained in denial, but now the diagnosis of inflation is becoming more widely shared. As to how this inflammation of our money could arise, I have devoted enough newsletters. But what could be the consequences and how do we fight this infection? Will we soon be able to get a free interest rate jab at every bank to prevent this inflammation?

The trouble with this inflammation is the feverish behaviour that inflation generates in us. If you have been confronted with significant price increases several times, you want to tame that animal and lose that money to exchange it for goods. Last week a shopkeeper in blinds* drew my attention to the possibly third price increase this year (of 5-15%), which I could better be ahead of… and so together we fan that fire even further….

European inflation since 1 January 2020

*Awnings are often made of aluminum. To make 1 ton of aluminum worth approximately € 2,500, takes approximately € 4,000 in energy costs. Aluminum factories are therefore shut down. Supply decreases with the risk of prices rising. So this is what stagflation can look.

Interest shows money’s value

While the ECB and the Fed still claim that inflation is only temporary, companies have started raising prices en masse. With the result that the inflation infection quickly becomes a contagious disease. Rising costs will always have to be passed on in order to maintain a profit margin. The pursuit of sustainability is also getting in our way, because we are investing less and less in oil and gas and we are (rightly) critical of mining. But it is precisely there that the metals are mined, which are necessary for, for example, the transition to electric vehicles. And so most inflation now comes from the lack of supply of raw materials, energy carriers and rising transport costs or logistical problems.

Low inflation is the best way to fight poverty, I have always been taught. Poor people usually do not have their own house, which can offer protection against inflation. An increase in energy costs will hit them hardest. They will therefore cry out loudest for higher wages. Central bankers, with their often unbridled urge for monetary growth, but also over-stimulating politicians bear a heavy responsibility to keep currency depreciation in check. Turkey shows us today what such an infection looks like in severe form. Unemployment is bad, but inflation, now 20%, is much worse: the population suffers badly and situations like these can even lead to a regime change.

What is the best fever reducer? First of all, the government must give us the feeling that money still has value: it must again be worthwhile to simply put it on a savings account in a bank. In short: the price of money, the interest rate, must be increased! Raising taxes on houses, as the president of DNB (Dutch Central Bank) suggests, even if the mortgage has been paid off in full, is putting the cart before the horse. Proposing fiscal policy because you have lost your monetary influence, says something about the state of the currency union.

An interest rate shot is the best remedy against this ‘house fever’, also a contagious situation by the way. I do, however, recommend to fix your mortgage interest rate first before you get the interest rate jab. Because yes, this shot is not completely without the risk of side effects. Financial markets are not immune to it either, although at this level of interest rates, these side effects might still be mild. Not much can withstand a really heavy dose of the interest rate medicine, but fortunately we are not up to those kind of interest rate winters yet.

The ECB cannot or does not want to keep the value of the euro

Lagarde does not want the shot, officially because she is deaf and blind to this infection. But in fact she is terrified that Southern Europe cannot handle an interest rate hike at all. With the huge government debts in those regions, that is understandable. The ECB therefore wants to continue buying the government bonds of these countries. The market can hardly compete with such a massive buyer in the bond markets, so what remains is the foreign exchange market. After all, the ECB can make much less of a fist there if the euro-dollar exchange rate falls. We are now already around 1.15-1.16 and unfortunately, that is also a new stimulus for (import-)inflation in the eurozone.

Bundesbank president Jens Weidman announced his resignation last month, 2 years before his term ends. As a hardliner in monetary policy, his hopeless minority position in the ECB must have been deeply frustrating. Will Klaas Knot, president of DNB, be next to throw in the towel? In any case, let’s be honest and say that there is little left of their function from a monetary point of view. Fighting inflation is apparently not a priority at the ECB for now.

Perhaps much later, when we have absorbed/federated most debts of the Southern European countries, maybe under the pressure of a falling euro, monetary policy can be pursued again. With the interest rate jab in time, well before inflation infection can rear its head. At this point in time, however, the major central banks as the Fed and especially the ECB, are at risk of lagging behind events.

Central Bankers – Bond Traders: 0-1

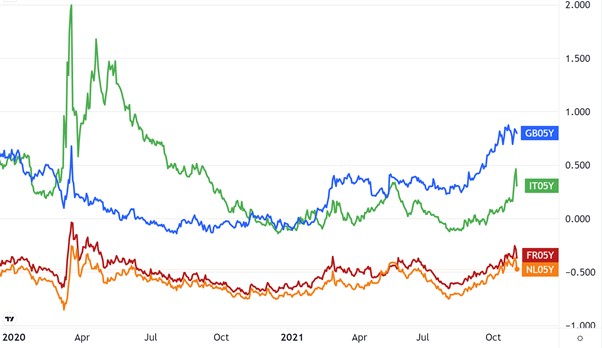

Incidentally, one could notice that many bond traders in recent weeks had also got their interest rate jab. See the graph below of rising 5-year yields in The Netherlands, Italy, France and the UK. Concerns in the market are starting to increase, although the stock market (despite some mumbling) seemed still hardly worried. In fact, equities in developed markets rose sharply in the past month.

5-year government interest rate in The Netherlands, Italy, France and the UK

The most striking interest rate development took place in Australia: here the central bank wanted to keep long-term interest rates around 0%, but was crushed by bond traders, who made short work of its policy and issued a significant interest rate jab. After an interest rate increase on 10-year paper of almost 1%! the central bank gave up. A statement about “changed inflation and market expectations” followed and the target of fixing long-term interest rates was abandoned.

What is the moral of this story? Central banks can set the trend for interest rates for a long time, unless they lose credibility: then the market will see through and they will be forced to rethink their policies.

So has your banker called you yet to receive your interest rate jab? And have you received another letter with a further tightening of the interest rate penalties? Tell him or her that a penalty interest on your savings account is unnecessary: the banks receive special interest subsidies from the ECB to avoid it.

I wish you a healthy interest rate environment!

BY: WOUTER WEIJAND, Chief Investment Officer