Think of stagflation as a series of increasingly expensive bottlenecks. Think of Schiphol Amsterdam Airport where there are not enough security guards and luggage porters so everyone gets stuck. Or the enormous lack of newspaper deliverers and cleaners, who can earn more elsewhere. Or to the increasingly expensive contractor, who can only start next year. There are also plenty of examples on the world stage. Like China, which country is paralyzed because of corona. Think of Russia that wants to produce oil, but is under a boycott. Or Ukraine that can neither produce nor export grain because the country is turned into a battlefield. Stagflation also occurs when it becomes too expensive to make something, such as aluminium or fertilizer, because the gas required to do is more expensive than the final product yields.

Stagflation creates a hole in the budget of producers and consumers. It is often accompanied by social unrest and strikes, as in the 1970’s. Initially, employees are still loyal, but if price increases last longer, the willingness to strike increases. In the current tight labour market, employers have hardly any choice, which increases the chance of a leapfrog effect and thus a wage-price spiral.

Monetary Intervention

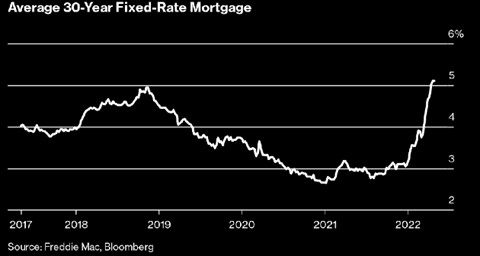

A substantial interest rate hike by central banks is often the only way to slow down this spiral and thus economic growth. An interest rate hike must also be substantial enough to curb labour-intensive construction and the housing market, for example. Because here too there is stagflation. Meanwhile, (mortgage) interest rates are rising almost everywhere, but will these new interest rate levels be enough to curb demand as long as inflation is so much higher? See below the development of the mortgage interest rate in the US, 30 years fixed, at an inflation of 8.5%.

But is such interest rate hike enough? Stagflation also occurs when everyone simultaneously places defense orders, which cannot be delivered quickly and will of course lead to significant price increases. Stagflation also occurs when everyone wants to go green at the same time and calls on scarce raw materials such as copper, nickel, cobalt, etc., whose stocks and/or production are limited.

Stagflation leads to a situation in which many parties increase prices, but without much immediate additional economic activity. So look at it as a series of increasingly expensive bottlenecks. Sometimes we create such a bottleneck on purpose: by throwing out Russia largely of the international SWIFT payment system, we cripple its central bank with the result that economic activity stagnates. The boycott of many Russian products is leading to sharp price increases and less production. This quickly becomes “stagflationary”, also for the Western world. Demand decreases there as well, because consumer confidence is being dented and producers are starting to have doubts. For example, there are increasing signs of a slowdown in economic growth, both in the US and many countries in Europe.

Russia uses stagflation as a weapon of war, as we do…

The failure of Gazprom to fill the ‘Bergen’ gas storage facility in The Netherlands was part of a brutal war strategy. It was a long-prepared action to throttle Europe’s gas supply and cause a price explosion if the war started. Putin knew perfectly well that Europe cannot do without his gas. An oil boycott does not amount to much and he must have taken this it into account. He knows he has the trump cards in this poker game. After all, we Europeans need years to prepare to do without Russian gas. And the price of LNG, which we will at some stage be paying to our American friends, has already doubled since the beginning of the war. So too much cheering here seems premature.

A war hurts on many fronts

Even the war stagnates and might go on for a very long time, with all involved paying a huge price, often the highest. At the same time we are playing for high stakes. Officially we are not at war with Russia, but never before have so many weapons been delivered that are used directly against Russia. And we, in turn, are outraged when Russia cuts off the gas supply to Poland and Bulgaria. Maybe it will be our turn soon. Apart from the risk of a military escalation and the deployment of even heavier weapons on Russian side, there is a real chance that Russia will turn off the gas tap for more and more countries. With Germany, the largest European economy, as the obvious victim.

At the same time, the war is increasingly affecting producer and consumer confidence. Even the US economy is cooling down: in fact, it even shrank in the first quarter, due to declining exports, higher imports and disappointing consumption levels. The massive lockdown as a response to the corona virus in China does not help either. World trade is stalling again and goods are quickly becoming more expensive. See below some images of stagflation trends in 4 major western economies.

Central banks started fearing (only recently) that price increases will continue for a longer period. Even the ECB is considering ending bond purchases soon and perhaps raising interest rates as early as July or August. Lagarde watched with sorrow when the foreign exchange market punished her monetary stumbling, because the euro/$ is now trading at around 1.05. And that creates even more inflation through higher import prices. In Germany, the counter is already at 7.8%, again higher than economists had expected. Bonds lost even more in value, about 3% last month alone. In the first four months of this year, the bond market fell by more than 8%, a historically large decline. Fortunately, we are defensively positioned here, with a low weighting and short maturities, but even we could not escape some price losses.

Profit development

It is interesting when it comes to corporate profits: those companies that can pass on the increased prices for raw materials, energy and labor can still show increased profits. But then, how temporary are the price increases? Take Unilever – an important company for daily shopping in our country – indicates that it will also have to continue to increase prices in the second half of the year. This will probably apply to almost all participants in these sectors. Since food and drugstore items represent a significant part of household consumption of lower income households, this will further erode real disposable income and further fuel calls for price compensation. This increases the risk of a wage-price spiral, especially in this globally tight labour market.

For the stock market, however, the earnings performance of large technology stocks is of much more importance. Here, earnings growth stalled and valuations took a hit. This prospect was the main reason for us to become more cautious on equities last year. For the time being, April took the ‘honour’ with a price drop of more than 8% of the broader S&P 500 index. The decline in the Nasdaq index of 13.2% with all its interest rate sensitive technology stocks turned out to be even greater.

Are price corrections now a thing of the past? Probably not yet, because if inflation really remains higher, say 4-5% in the longer term (against 8.5% now), we will not be there yet with 3% for the 10-year interest rate in the US. Wages are now also increasing by 4-5%, as the chart below shows. From a historical point of view, this is a significant acceleration.

The concerns of central bankers will remain high for the time being and we cannot count on the ‘Fed put’. We therefore remain defensively positioned, remain cautious on bonds and hope to re-purchase equities at lower levels.

And meanwhile, our alternative fixed-income investments in Consumer Loans are getting closer again: these are characterized by low interest rate sensitivity, high remuneration and a very diversified credit risk. We hope for a yield of 5-6% annually. Our Real Assets, such as those in Infrastructure, were up 1.8% in the first quarter in local currency. The rise in the US$ and other foreign currencies still to be added. In addition, our Private Debt funds offer consolation where bonds actually fall sharply.

Markets do not seem to be getting cheerful in this ‘war year’. And I have not cheered you up either with the above story. But sometimes it is no different. Needless to say, we remain relatively cautious.

BY: WOUTER WEIJAND, Chief Investment Officer