What went well and what could have been better? Financial markets started the year on a positive note: bonds were in demand, if rates fell. Equities saw a way up, after a difficult 2022. The first bump came in March, when a minor US banking crisis took place. Doubts about the solvency of small banks, which had often bought government bonds when interest rates were much lower, led to hefty deposit withdrawals. The Fed intervened and provided credit support. We bought a tracker of bank stocks, which was down by about 1/3. After quite a few fluctuations, this investment ended the year about 12% above the purchase price.

Then the fall in bond yields came too soon, as inflation appeared to be far from contained during the year. Both the Fed and the ECB felt compelled to raise money market rates further, to 5.25% and 4% respectively. Our cautious stance still proved correct. Only at the end of October did we ‘reverse’. We believed we had seen the peak in inflation and bought (medium to) long-term US government bonds, hedged into Euro. The timing proved right, although we could have extended the duration of the bond portfolio even further. Nevertheless, we made an outperformance with our fixed-income portfolio. Hedging the dollar also proved useful, as this currency ended the year close to its lowest rate of the year, around 1.11 against the euro.

The choices within the equity portfolio turned out less well. Overweight positions in Emerging Markets and China hurt. While prices rose in most developed countries, they fell 17% in China. The property crisis there continued and economic growth was disappointing. Yet even the central government seems to realise that too much intervention in the market mechanism does not help. A low current valuation is another reason for us to remain invested here.

While equity markets in Europe and the US got excited by the fall in bond yields, we did not chase the rally. We took into account the economic slowdown in Europe and the risks for a cooling down in the US as well. Markets, by contrast, are already pricing in much more interest rate cuts by central banks than we consider likely. All in all, we lagged behind our equity benchmarks.

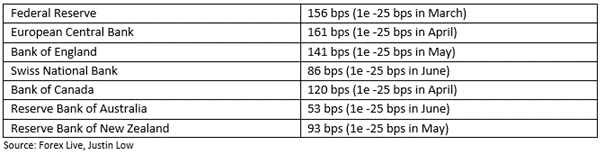

How many interest rate cuts have already been priced in? These were the figures on Boxing Day:

(shown in brackets by how much and when the 1st interest rate cut is expected)

It is with this sceptical feeling about the interest rate cut that we cross the threshold into the new year. After all, why cut interest rates as a central bank when mortgage rates globally follow interest rate declines in bond markets? Effectively, that is already considerable monetary easing, boosting housing markets and the investment climate. Both could use a boost. What is the potential for long-term interest rates in Europe when 10-year German government bonds are not even yielding 2%? Hasn’t the market surpassed itself here? In fact, long rates here discount a 4% cut in money market rates to below 2%. Equally long-dated US government paper, at just under 4%, looks a lot more attractive than European long rates.

Less generous governments

In recent years, both citizens and companies have benefited enormously from generous governments, which have reached deep into their pockets to help solve or mitigate all kinds of crises: there was a corona recovery programme with wage subsidies, there were energy price caps, there were generous tax deferrals, but now the party is over in Europe. From now on, the usual fiscal rules apply again. In the US, Santa Claus is still not gone and even in 2024, the budget deficit there will be 7-8%, compared to around 3% in Europe. This cannot continue much longer, of course, and Republicans in particular promise to put an end to this as soon as possible, at least if they were to regain power after the November 5th elections.

Biden or Trump?

The many polls keep Trump and Biden roughly in balance. At the Economist (poll 1 January 1), both candidates score 44% and at Morning Consult (poll 31 December), Trump scores 1% more than Biden. Interestingly, there is more disapproval than approval for both candidates in the US. In this, Trump enjoys 10% more disapproval, but Biden as much as 15%!

So, whether Trump can seize power again is still uncertain. Many lawsuits await, so first he should just try to stay out of jail. The repercussions of his eventual return will be huge. He does not like Ukraine nor defence aid to that country. Ideally, he would like to strike a deal with Putin, which could make the loss of land in Ukraine permanent. US membership of NATO is also in question with Trump’s arrival. Europe will be more reliant on itself than ever before. With that, does China see its chance to re-engage Taiwan? “America first” for Trump means at most some extra trade measures against China, but not the support for Taiwan that people there have been used to from the US for years.

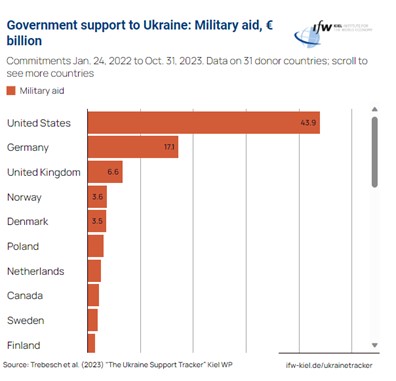

Military aid to Ukraine in 2022 and 2023, and what Europe may have to take over from the US if Trump comes to power?

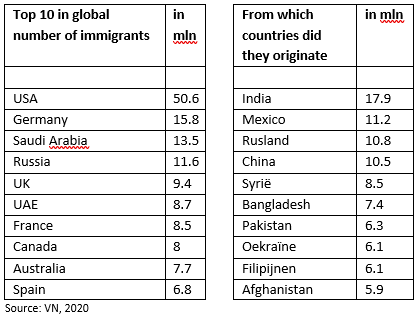

Even if we wanted to, we do not have the military capacity in Europe to give Ukraine that much support. So, in geopolitical terms, 2024 will be an exciting year. After all, of all the wars, we only overcame the war on inflation in 2023. As we cross the threshold of the new year, there is also the silent battle, which we all eventually lose: ageing. We are getting another year older, and more people are leaving the workforce than entering it. Quietly we know that only immigration can solve the labour market shortage. But judging by the election results, we don’t want that. Just as it is the case almost everywhere else in Europe. In the US, they also pretend not to want that, but quietly millions of immigrants cross the Mexican American border every year. Without this continuous influx, US economic growth would have been lower and inflation even higher for year.

No surprising lists, both in terms of outflows and inflows. Fairly evenly distributed globally too. So, it’s not the numbers, but the political resistance, which varies a lot from country to country. Where, especially in Europe and Australia, one cannot match the Canadian enthusiasm for new compatriots.

Who is going to stop this flow?

And speaking of (in)flows: the Dutch city of Deventer has not been swallowed: a mere 9 cm was left over after Holland, as the plughole of the European monsoon, had to resort to increased dike surveillance. Climate predictions, such as a 1.5% increase in temperature or sharp increases in precipitations – once a threat in a distant future – have already become reality. It feels like we have already been overtaken by the facts and we are still quickly trying to stick a finger in the dike. Of course, we are always left wondering where best to invest. Still, it would be practical if we first determined where best to live….

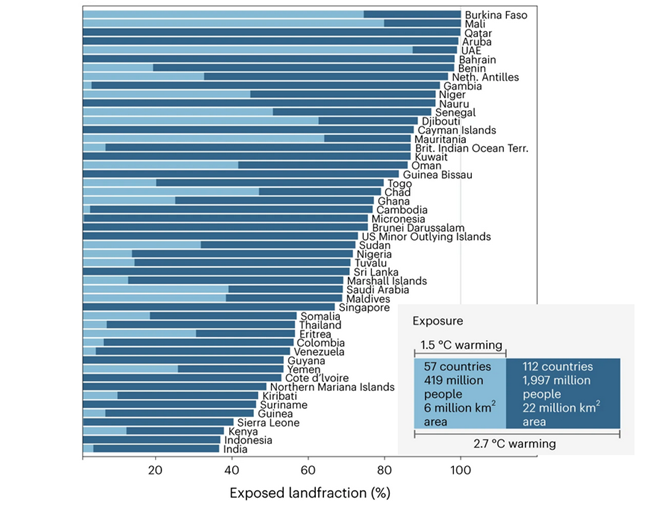

Territory of countries (% per country) affected by extreme heat

Joint research by the universities of Wageningen, Exeter and Nanjing points to the risks of a 2.7 degree rise in global temperatures if stricter climate measures are not taken. If so, a good part of the habitat of 2 billion people will become unliveable hot by 2100. Above you can see the list of most affected countries, which is hardly part of our investment universe. But that doesn’t make it less sad and disastrous for these 2 billion people.

How does this concern me, you may ask? What about the Netherlands, anyway? And what will this climate change cost me? How is climate change priced? As an encore at the start of the new year, below you will find a little story about a possible price of climate change in the Netherlands.

Despite all this, I wish you a Happy New Year and express the hope that as recognised water builders, we will manage to keep the doomsday scenarios ahead of us for a long time to come!

And so, we’ll just go on to the order of all investment days of the year anyway, when we sell at low water and fresh weather and buy back at high water and heat….

We wish you all the best for the new year!

DOOR: WOUTER WEIJAND, Chief Investment Officer

Addendum: on the threshold to a new year in response to climate change

Does everything have a price? And who pays for it?

Everything has a price, it is sometimes said, but does it? Last year, the top prize went to AI, Artificial Intelligence. Markets gave AI an increasingly higher price because they were able to put a price on AI developments through sharply higher share prices of Tech stocks, who responded to it. Whether they are worth that price, we don’t know, because those future benefits of AI are hard to estimate. And as often before, the stock market took a guesstimate.

Next to that, there were all sorts of spectacular climatic developments, for which there was hardly any price to be found. Disasters were plentiful, but what do they cost and who will pay for them? Of course, together we help pay for dike reinforcement and coastal defence through taxation. That is the public price we are willing to pay. But what about defending our personal property, if damages from storms and floods continue to increase? Then insurers usually drop out and your house becomes uninsurable. Florida is already proof of that. In many places, there is already no price, no insurance premium high enough to assess the risk of damage. From then on, you are at the mercy of the gods.

It could be similar in Holland: if Deventer, Hoorn or Volendam had really been flooded, many would have been left in the cold by their insurance companies. Crying out and begging for help is something we usually only do to the Government in The Hague.

This creates the picture of substantial prosperity disappearing into private pockets and unpriced adversity being passed on to the community. Such a thing is then called ‘bad luck’, like the corona epidemic and we all pay for it. But is that justified, or shouldn’t there first be an adjustment of property prices? After all, you don’t need to be an Einstein to understand that you are at much greater risk close to a river or sea than on the higher areas of the country… And that the Netherlands and Bangladesh face greater flood risks than Scandinavia and Spain.

We will have to decide as a community to redesign our country. We may have to relocate whole tribes. On the other hand, we cannot keep passing our own sometimes questionable real estate decisions onto the collective endlessly. For instance, the foundations of many houses in our country will have to be renovated. And at the cost of often 100K per house is not going to be paid for by the government, I suspect. On the other hand, the extra expenses of the Water Boards will again be borne collectively, but then again paid by ourselves.

Eventually, if the water continues to rise and no matter how hard we try to defend ourselves, we will sometimes have to leave behind parts of our delta and our villages and towns. These will then literally become “stranded assets”. There is then no longer a price to pay for them. Unlike farmers, there are too many of us to all be bought out. Our country, at least our population, will one day have to move a bit eastwards, with a new coastline being formed by the hilly forests in the middle of the country.

Does any financial advice apply to that, by the way? Yes, although its timing is very difficult to estimate, renting will at some point become more attractive than buying, in those vulnerable areas. Gradually, property markets will start pricing in all those kinds of vulnerabilities, locally and internationally. The fall in prices in the West when selling and the price rise in the East when buying, will be for your own account.

In the meantime, I wish you many happy years, with that ‘priceless’ beautiful sea or river view from your living room!