A few years ago, the financial world was as beautiful as Goldilocks: self-evident growth and low inflation. But it looks like it’s ugly stepsister has taken over. The manufacturing economies of this world are struggling. The West is ordering less, so the East, starring China, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, is getting fewer export orders. Activity is declining and inventories are rising.

Looking at this situation through Western glasses, we see that the inflation ghost and increased interest rates are taking their toll. Consumer and producer confidence is falling. The property boom is over, and construction is at a standstill in many countries. Besides China, incidentally about the only country where interest rates are falling, this is now the case in Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands, for example. Property developers shut down or worse after such an interest rate hike. They then cancel their construction contracts. Not to mention tax disincentive policies, as we know them in the Netherlands.

Meanwhile, in Europe, we went from a pandemic-low and subsequent boom to stagnation, but with inflation, that by the way, rose again last month to 6.5%. Stagflation is what we call it. In China, prices are falling, but that is an exception. In the US, prices are still rising, but less so than in Europe and the labour market is starting to cool off slightly. Job growth continued, but at a slightly slower pace. Even vacancies fell, although their size remains an awe-inspiring at 8.8 million.

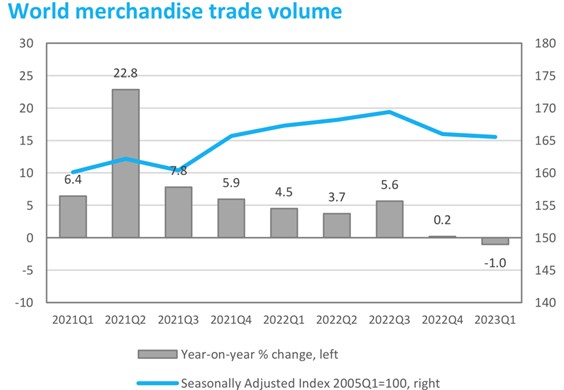

This is the economic cycle, which is affecting global trade with its ups and downs.

World trade slows

The graph above shows the recent downturn in world trade: we do not yet know how much of this downturn is cyclical and how much is structural in nature, but historically, an annual 5% growth in world trade was quite common (exceptional in 2021, by the way, was the post-corona recovery, which compensated for the decline in 2020, not visible here). Bear in mind that the most open economies, i.e., with the most international trade, are also the most sensitive to fluctuations in global trade. These are mainly developing countries and Europe. The USA, as a very large country, has a relatively small external sector, of around 15-20% of its economy.

But what are the structural developments which play a role in the waning global trade?

First, geopolitical changes. The war in Ukraine is costing a fortune and is eroding confidence. Europe suffers the most. Then there is the tension between China and the US. All the sanctions and boycotts make global trade less efficient and therefore more expensive. For the new iPhone 15, for example, brand new factories have been built in India, Vietnam, and Taiwan in 2022. Each with hundreds of suppliers in their vicinity. This is very costly and makes logistics more complicated and the final product more expensive.

The fragmentation in Apple factories in 2022

While 10 years ago, 80% of Apple’s suppliers came from China, today it is a very mixed picture. Not that China now has fewer factories working for Apple, but Apple factories are now more spread across Asia.

Every man for himself

In Europe, for instance, we are building a huge chip factory in Dresden to make Europe more independent from external chip supplies. Everyone wants to become more independent, with more production in their own region. That will be an expensive endeavour for everyone. The free global trade that we enjoyed for some 30 years seems like a relic of the past.

Emerging unions and creaking public finances

Then there is the re-emergence of trade unions, as guardians of workers’ purchasing power. That tells us something about middle-class stress. Globally, unions are pushing harder for wage growth and price compensation. It is succeeding, too, because employers know how tight the labour market is. So, wages will continue to rise for now, but can companies still pass this on through higher prices? Especially in this weakening cyclical phase? Finally, there are the creaking public finances worldwide. The rise in interest rates also makes government debt more expensive. Companies will complain more, their margins and profits will come under pressure, as will their sales, especially in manufacturing. But governments today do not have the money to step in. Consumers can also face tax increases, which can drive up prices.

This is where structural factors hit the business cycle. Central banks are considering to keep interest rates high for longer because inflation is not falling enough. While in part it is also structural developments that keep inflation higher than desired.

Financial markets were quite volatile last month. First, there was the downgrading of America to AA+ by Fitch and interest rates rose further on fears of persistent inflation. This did stock markets no favours. Then, many economies showed signs of cooling and people took this as good news. Interest rates fell slightly, and stock markets recovered. Is this justified?

Goldilocks will not return for a while

Sure, this dip in the business cycle is depressing inflation, but structural factors are driving up prices.

I think central banks will eventually have to adjust their inflation ambition from 2% to 3%. Looking back later, we will consider the period 1990-2020 with its low inflation not only exceptional, but mostly over…. Perhaps still with a soft landing, but without Goldilocks, with that stable growth and low inflation.

In summary, this is the reason we are cautious with our bond investments and have gradually become more cautious with equities as well. Our previous argumentation played a role here, but, more importantly, so did increased valuations. Incidentally, stock markets took little notice of our waning enthusiasm, while interest rate markets did. While we remained well ahead of the benchmark last year, this year we are missing out on the equities side. This is mainly due to the overweighting in Emerging Markets and our underweighting in US equities, which continued to thrive. While our illiquid investments managed to keep up with interest rate markets but not with stock markets.

Central banks will get the economy down and if not, governments will help, as they are tightening their belt. But even if we look beyond the (coming) downturn, we will probably have to do without Goldilocks. She is waving us goodbye: hopefully we will meet her stable growth with low inflation again.

BY: WOUTER WEIJAND, Chief Investment Officer