It is no longer news that January brought a cold wind over markets. One that came from the Federal Reserve, which decided to let the wind blow from a different angle. No more endless money creation, the tap in the US is closing even faster than first announced. Moreover, the price of money could also go up faster. Plus money could soon be withdrawn from the system. So from years of high tide we are now quite suddenly heading towards low tide. The market had to get used to that.

“A rising tide raises all boats” is a well-known saying in our profession. In my previous newsletter I already showed you the price movement of a classic boat, the ARK Innovation ETF. Was it the flood of money, which propelled its price, before the ebb tide halved its price? In other words, were these just speculative, unprofitable tech stocks that fell through when interest rate stress made itself felt?

ARK Innovation ETF price chart, as of January 1, 2020

The Financial Times analysed all the underlying tech stocks in the fund (source: Unhedged, column dated January 31, 2022). The earnings growth was not too bad, it was often substantial. The valuation too, I may add. See the graph of the Nasdaq-100 further down.

At the same time, it was the favourite toy of a large group of new, young investors. Who mainly get their ideas from social media. With brokers like Robinhood, which itself halved in price, as did all kinds of crypto currencies and related companies. But also with companies like Netflix, Spotify: young, growing tech companies, with all kinds of growth spurts and issues, in which young people pumped a lot of money, but also withdrew it just as quickly. It is partly real fundamental technological development, but also partly purely liquidity-driven financial markets, that helped determine the ups and downs. Whereby ARK already loosened up in the last few days, supported by new inflows of money.

Growth stocks and money politics

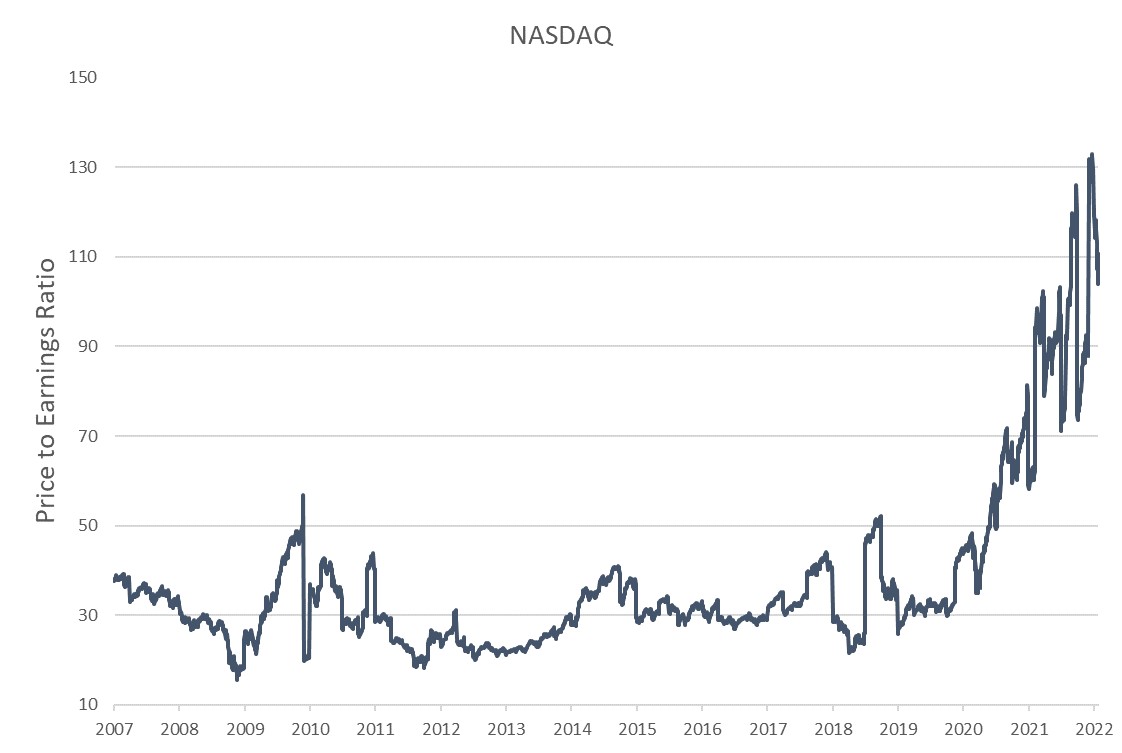

This brings us to the heart of the discussion about growth stocks and monetary policy. Too much money growth causes inflation, including in equities. It necessitates interest rate rises and thus erodes the valuation of cash flows, which lie in the distant future. As is the case with tech stocks. Especially if central bankers also want to withdraw money from financial markets. The profits themselves will continue to grow (see e.g. Google), but rising interest will probably lower the P/E ratio. After all, the one below looks rather extreme.

P/E ratio Nasdaq since 2007

That’s what happened in markets in January. It also explains why we were underweight bonds and equities at the same time. Because even though bonds did not make the front pages of the newspapers, they were also under water due to higher interest rates. Below are the results of Dutch and US government bonds in the 2-, 5-, 10- and 30-year segments, in local currency, for January.

Government bond performance, in local currency, for January 2022

What do we offer in return?

Alternative fixed income sources such as factoring and consumer loans, for example. With very low interest rate risks and well-diversified credit risks, the current inflation rate of 5-6% can probably be beaten. Private Debt can also get close to those returns.

Investments in Infrastructure, including power plants, solar and wind farms also offer protection against inflation with a dividend of around 7%.

The real interest rate rise is still to come

However, a serious interest rate hike has not even taken place yet: this was just Spielerei with interest rate hikes of a few tenths of a percent. Of course, this is the discussion of the day among strategists: how much should interest rates rise to get the inflation ghost of 5-6-7%, back in the bottle? Or has it really escaped now, roaming around in gas companies, in raw materials and semi-finished goods, in transportation and supermarkets. Above all, consider rising wages. This is what the Federal Reserve is most afraid of, also because the labour market is tight. This is the case in many countries, by the way. Inflation in this new year is becoming significant, as many companies only raise their prices at the beginning of a new calendar year.

So pronouncing loudly that inflation will not rise will not get you very far, as ECB President Christine Lagarde now knows. Because even though European inflation should have fallen from 5% to 4.4% in January, it became 5.1%, again much higher than all those economists had expected. In The Netherlands last month we carelessly went from 6.7% to 7.6% inflation, a shocking number.

Yet Lagarde leaves the money tap generously open and encourages governments to open the fiscal tap wide as well. Across Europe, government spending is going up spectacularly, even in The Netherlands and Germany. Could it be that the realization has dawned on us that we will have to bail out Italy in any case, and that we’d better do so with an almost as empty treasury? So we can first enjoy our old savings for a while? Either way, a wide open fiscal tap does increase inflation and the resulting wage increases. As the people and materials, needed to carry out the-billions-devouring plans, are often not available.

Geopolitics and inflation

Next, there are geopolitical sources of inflation, with Putin versus Europe a crucial factor. The further this conflict escalates, the higher oil, gas and electricity prices will become. Threatening Putin with a blockade of the Nordstream 2 gas pipeline looks brave, but awkward, because many European countries are now dependent on Russian gas, Germany first and foremost. Will Europe soon leave itself out in the cold?

Nobody knows how this conflict will end. I fear for a rather small, permanently continuing occupation, in which the West will not intervene. Where at the same time the military sting remains, but the fear of a large-scale conflict may gradually run out of energy prices. Still, broader inflation will have settled into everyone’s expectations by now. We will not get rid of it that easily.

The debate over inflation and the ebb and flow of money creation will not simply disappear. The managers of Norway’s huge sovereign wealth fund think it will have repercussions for longer-term bond and stock prices. One month does not make winter, they may think in Norway. If it is allowed to become spring on financial markets, we foresee this for equities earlier than for bonds, where the temperature has been below zero for years now.

BY: WOUTER WEIJAND, Chief Investment Officer