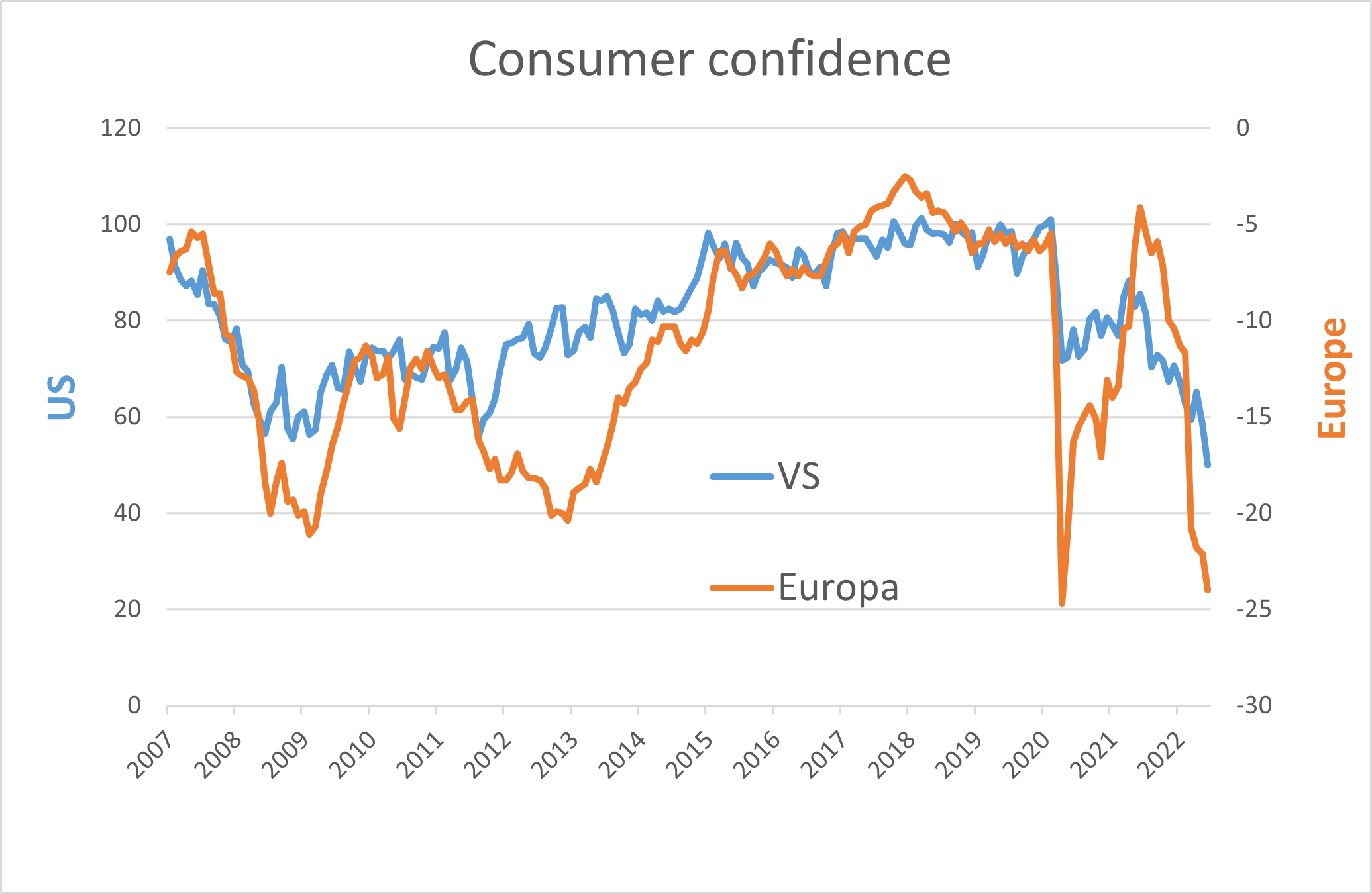

For months, I have been tiring you with stagflation risks and now economies are stagnating not only in Europe (The Netherlands, Germany, France), but also in the US. The official growth figure for Q1 was even negative. In addition, the decline in consumer confidence is striking almost everywhere. This is logical, given the continuing inflation, also in June, because it does not make any citizen happy. And then there were rising interest rates. The sharp rise in mortgage interest rates is affecting confidence in the housing market, which seems to have started cooling in many countries.

Fast forward to today, financial markets thought that a recession would be inevitable and commodity prices plummeted: especially metal prices, but luckily also food prices. Oil and gas prices also fell, but in Europe Russia keeps energy prices in an iron grip. Gas supply to Europe was cut off further and gas prices are now 4 to 5 times higher than in the US. Consequently, European electricity prices continued to rise as well.

Nevertheless, interest rate markets even started to price in an easing of monetary policy around 2023-2024. First, interest rates would rise, but then they would fall again, because inflation would no longer be the main problem. No, perhaps a recession was inevitable. That is what the bond market and implied forward rates are now telling us.

Equally so, many strategists seem to throw in the towel these days when it comes to their risk appetite. Whereas in the past six months they were still mostly optimistic, whatever the setbacks, recently the bear has been loose. Recession is the magic word here, the “fear enemy” if you like. Whether or not it has already been partly factored into financial markets after a fall of 20-25% is something you read less about. But fear reigns supreme in Europe, where the euro has become the target of investors who do not believe that the ECB can really raise interest rates much in this climate.

Stock markets

We see two phases in the decline of stock markets. Phase 1 is the correction in the overvaluation of equities: far too low interest rates had led to excessive price/earnings ratios and a disappointing inflation would force central banks to raise them again, so that stock prices would come down to earth again. This phase has in any case taken place.

Phase 2 is uncertainty about corporate profits in a climate of stagflation. Is it possible to pass on higher wages and raw material prices to consumers in order to preserve profit (margins)? Suppose that prices rise by 8%, but production volume decreases by 2%, turnover will still rise by 6%. Out of which the higher wages and input prices must be paid.

But that is macro, on a micro level it can work out very differently. And there seems to be a shift from the goods economy to the services economy. In other words: we do not order stuff for a while, but spend more on holidays. Which, by the way, are also becoming much more expensive.

So far, there is no sign of a profit recession: companies are reporting very mixed results. Stock exchanges are particularly impressed by declining consumer confidence and are pricing in some of the declining corporate profits. How much we do not know exactly.

A little cooling cannot hurt

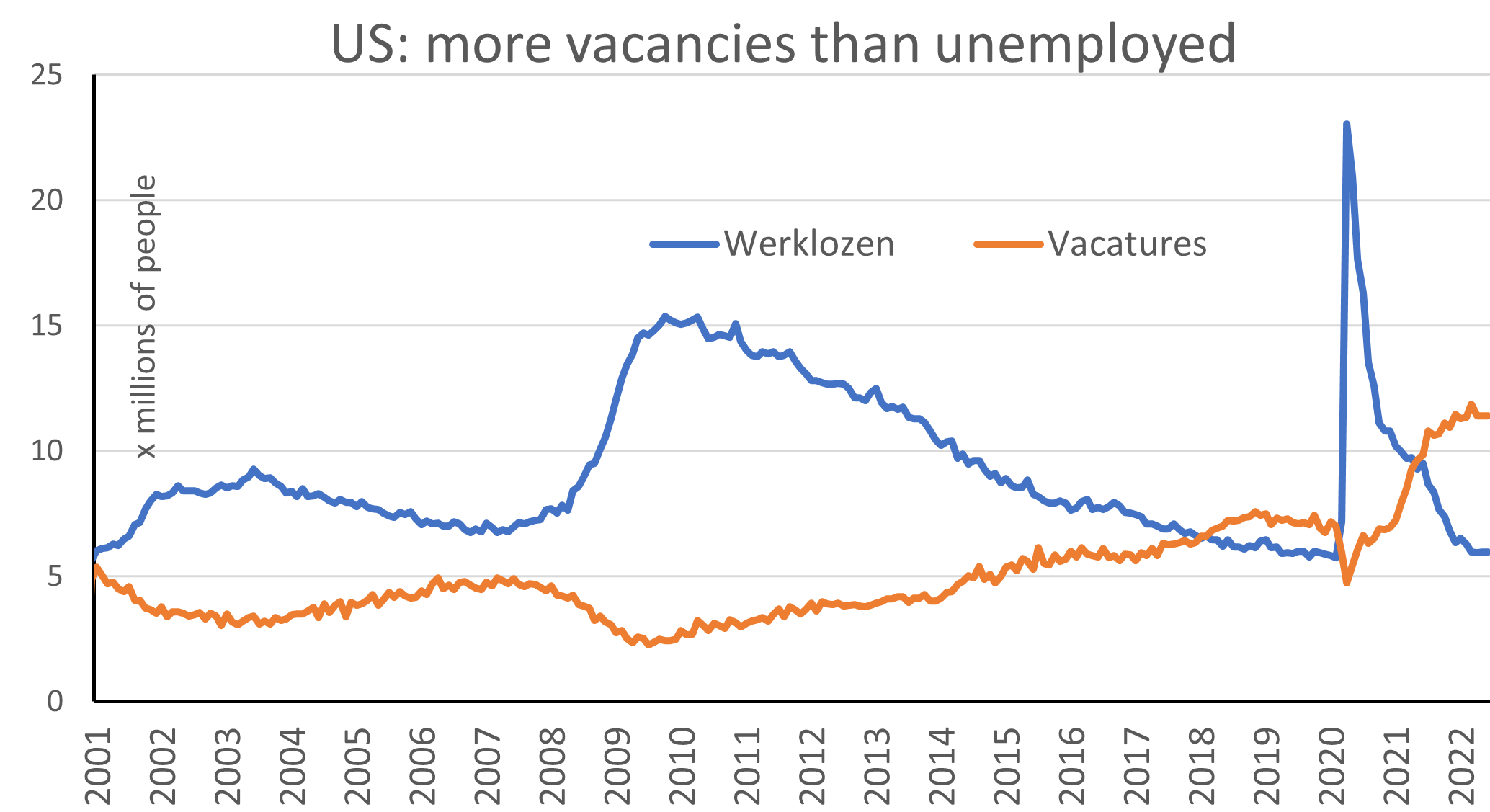

But how are wages developing with the current shortage on the labour market? Wages initially lagged inflation but are now catching up: at around 4% in Europe and 5-6% in the US. Admittedly, this does not eliminate the pain of the real wage decline, but the labour market is still so tight that higher wages can often be easily achieved elsewhere. Even at the bottom of the labour market, (minimum) wages are being pushed up considerably in order to alleviate the worst suffering.

In many countries, companies will therefore have to pay and will receive fewer tax breaks. But will this lead to a recession at an average nominal sales growth of say 6%? With interest rates of about 1.5% in Europe, 3% in the US and 0.25% in Japan? All figures relate to 10-year government bond yields, which have already fallen back significantly in recent weeks. To that end, let’s look at the job vacancies in the US, although the picture will not be very different in many other countries.

The excessive monetary and fiscal stimulus of recent years has led to an overstrained labour market worldwide. Perhaps a cooling of the labour market would provide some relief in many countries: there are staff shortages everywhere and some sectors have sometimes literally grinded to a halt. Not because of too little demand, but because of too little supply. Stagflation therefore rather than recession.

Consumers on the brakes, governments full steam ahead

Another factor that argues against a recession (yet) is the enormous expansion of government spending worldwide. Now that the pandemic-related spending wave is behind us, inflation is the new reason to pull out the wallet. Politicians are making every effort to compensate for price increases: price caps, subsidies, VAT reductions, etc. In addition, defense spending is being multiplied and the energy transition has yet to begin. Budgetary norms are being smoothly set aside and the rise in interest expenses is still hardly taken into consideration by any country. All bills are carelessly shifted into the future. So even if consumers and businesses were to tread water, the government is going full throttle everywhere.

I think that is why markets are too early to expect lower interest rates now because of this supposed recession. Inflation rates remained high in June and will need a bit more time to really start falling. Central bankers will not want to take the risk that the “fire contained” signal will be given too soon, something Fed Chairman Powell explicitly referred to. Whether central bankers can really achieve a “soft landing” of the economy remains to be seen. Higher interest rates will cool housing markets and there is a risk of (unexpected) capital losses. But let us not pretend that economic fears have not yet been felt on stock markets.

Last month was another volatile trading month, in which we again operated on the buy side. For the first time in many months, we are neutrally positioned in equities. Not because we are jubilant with optimism. We realize that corporate profits are now less predictable. But at these lower price levels, we no longer want to be underweight equities.

In bond markets, the situation is different. Although much blood has already been shed, we find it hard to imagine that at current still paltry interest rate levels on government bonds, the rise in interest rates will have ended. Here, along with the terrible war, lies the greatest risk for stock markets.

In the meantime, interest rates have already risen sharply for some categories of bonds: for High Yield and Emerging Market Debt bonds, interest rates are already in the 8-9% range. Because we had opted in this sector for short maturities, the price losses were smaller, but still rather noticeable. It also explains our recent investment in Consumer Loans, given the modest interest rate risk at a duration of 1-1.5 years.

But is there perhaps any good news in these gloomy times? Yes, and it is from an unexpected source, but China offers bright spots. Not only have they been easing monetary and fiscal policy for some time now, but they have also taken the economy off the pandemic lock. This will soon be noticeable in this enormous production and exporting country and thus also in the rest of the world. The bottlenecks in all kinds of supply lines will decrease in size. Trade flows will start up again. The prices for container transport (Baltic Dry Index) have already fallen to the levels of before the pandemic. Meanwhile, the Chinese stock market made a big jump (+11%), while the US and Europe recorded about -7%.

Finally, one should not get too excited about the differences between stagflation and recession. To me, an end to the war seems more important for stock market sentiment. It would take the sting out of inflation and help restore confidence among businesses and consumers. I certainly do not rule out stock markets going even lower and maybe then we might even install an overweight position in equities. Sell high and buy back low, I know how simple it sounds, but in this business it is still something to pursue for the longer term.

BY: WOUTER WEIJAND, Chief Investment Officer